From the Ship

Stories of the Black Mist: First Nation anti-nuclear activists share testimonies on Peace Boat

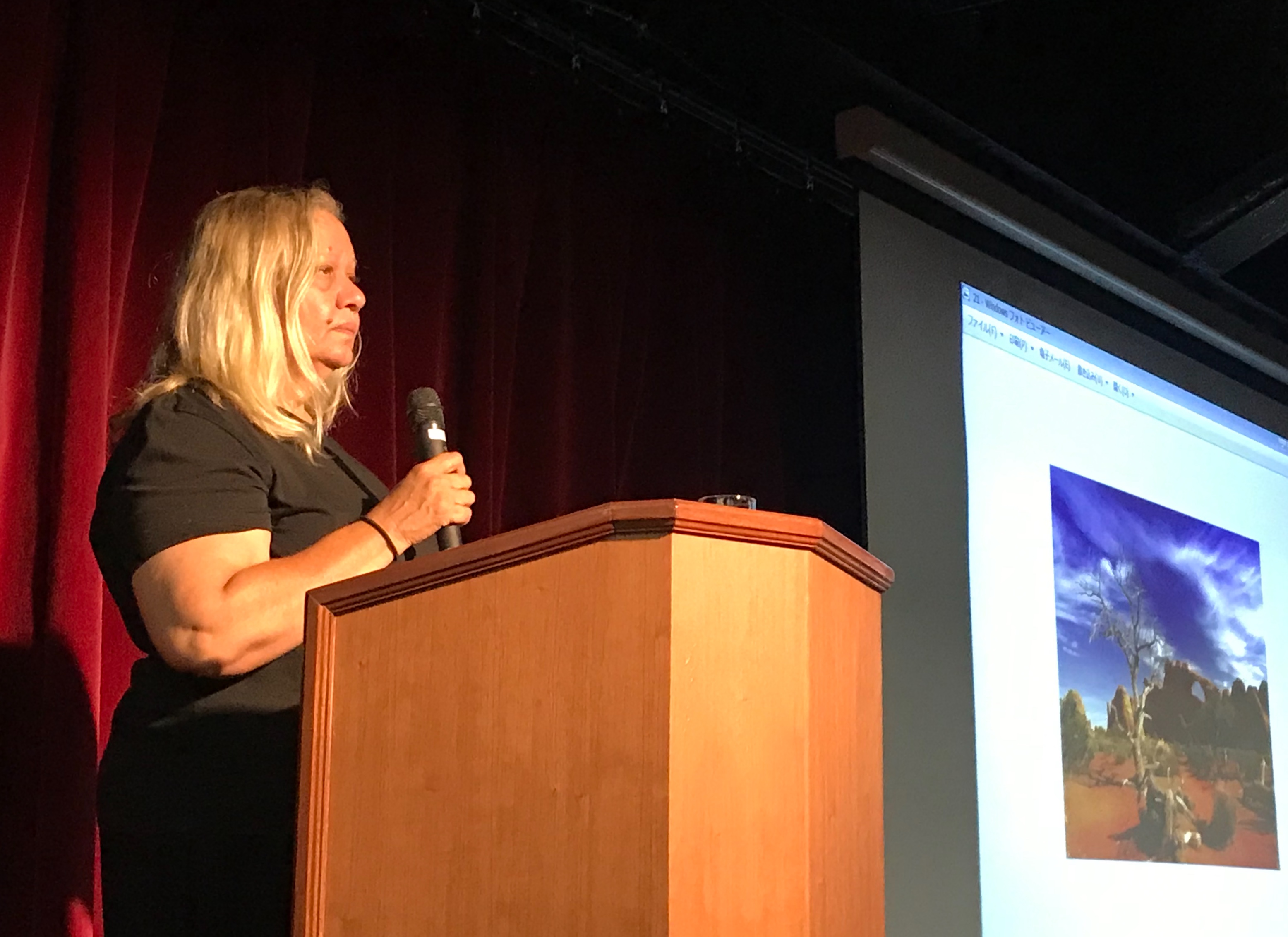

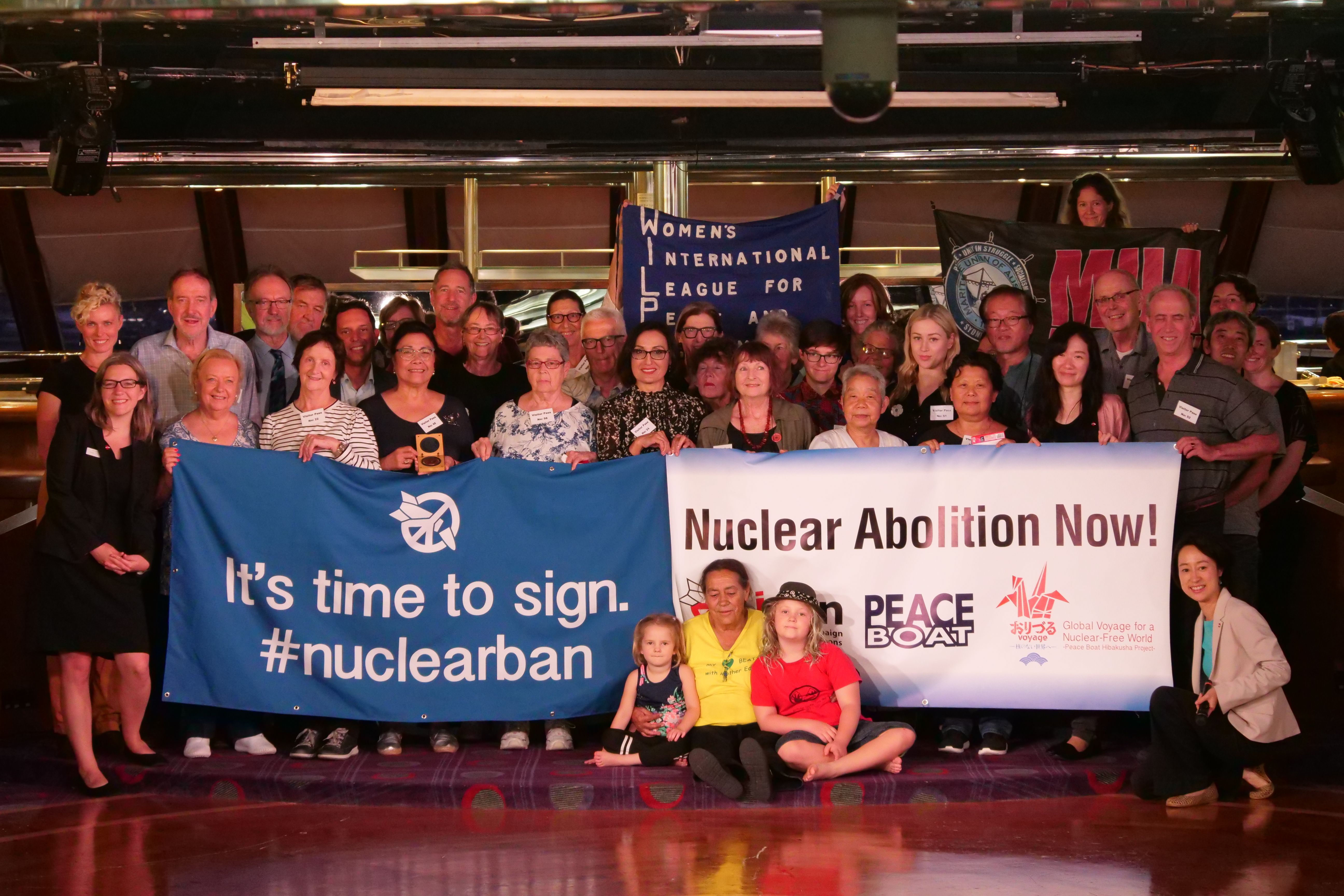

The fight for Australia's land – and a nuclear-free future – is being fought by the same people who have guarded it for tens of thousands of years. Joining Peace Boat's 103rd Oceania Voyage through cooperation with the International Campaign for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) Australia were Debbie Carmody, who stayed with the ship for five days in Fremantle, and Sue Coleman-Haseldine, who traveled on board from Adelaide to Sydney. They are both indigenous Australians who have devoted their lives to fighting for the rights of their people and the future of their country, and they used their time on board to share their stories of survival and activism.

Debbie, a member of the Anangu and Spinifex nations, manages Tjuma Pulka First Nation Radio Station, a radio station based in Western Australia dedicated to promoting the music and voices of indigenous people. Spinifex Country – Tjuntjuntjara – is made up of 55,000 square kilometers in of what is now known as the Great Victoria Desert.

Aunty Sue, a Kokatha Mula elder, was born on the Koonibba Aboriginal Mission in 1951. Kokatha lands are 140,000 square kilometers of plains and desert in South Australia, just north of where Sue lives now in Ceduna. Her people's sense of stewardship towards the land has nnever faded. “We still carry on looking after our country as our people always did, even though we don’t live out there now,” she says. As an elder she helps teach the young people of her country about living off the land and caring for it, as the Traditional Owners have been doing in Australia for thousands of years.

That land – along with the people who have cared for it – was forever changed in 1953, when the first atomic bomb tests began in Emu Field and continued in a place called Maralinga, in Anangu country. The British and Australian governments chose these test sites, Aunty Sue says, because these lands were considered an empty 'wasteland', despite their significance – and proximity – to the first nations people of the area. “For all of [the Aboriginal groups of Australia] our land is the basis of our culture – it’s our church, our grocery shop, our schools, our chemist,” says Aunty Sue. “But living a life and practicing culture out in the desert wasn’t recognised as worthy by governments back then, or still today.”

Despite knowing these communities lived in the area, the government did not tell Sue or Debbie's people what was being done. The Anangu and Spinifex people were told to leave their home in Ooldea in 1952, but were not told why, and were not given a place to go. “My people became refugees,” says Debbie. Some families continued to move within their traditional lands. Hazardous areas containing high radiation levels were poorly monitored, and signs warning people away were only in English.

The first bomb, known as 'Totem 1', was dropped in Emu Field on October 15, 1953 when Aunty Sue was two years old. The fallout from that bomb would be carried by a dust storm known as 'the Black Mist', a radioactive cloud that would contaminate land, water and wildlife, and sicken those who came in contact with it. Many people fell ill, were blinded or even died, while others would develop complications such as cancer, thyroid conditions and bowel problems years later. Fertility problems, birth defects and infant mortality rates all rose. The effects of the two nuclear bomb tests in Emu Field and the eight that followed from 1956 in Maralinga continue to this day, though limited studies have been done to measure the full scope of the impact. Sue says there is still “wonder and worry” about genetic changes caused by the radiation being passed on to future generations.

The Anangu and Spinifex people share stories of the bomb and the Black Mist as well. “They were all very sick,” Debbie says. “No one could walk. Everyone was just crawling around. All we knew was that the wind had brought in this terrible sickness.” Her people tell of birds falling dead out of the sky and finding animals cooked from radiation. Because people did not know what was happening, they would eat these animals, and become sick.

In the 1950s a missionary by the name of Bob Stewart established Cundelee Mission at the edge of the Victoria Desert in order to “educate and Christianize” the Aboriginal people of the Western desert. Stewart would make trips into the desert to 'rescue' Spinifex people and bring them to the mission. While Cundelee did deliver them from radiation, the mission itself was cramped, with little water or food, and sought to convert the refugees to Christianity. “It was a bad place and no one was happy,” says Debbie. “We inherited a social disaster.” Her people wouldn't be able to return to their land until the 1980s.

While the time of nuclear testing is long past, Australia's ties to nuclear weapons and power continues. Uranium mining continues to displace communities and contaminate the surrounding environment, and poses a threat to people outside Australia as well. “Fukushima started in the back of dump trucks in Australia,” says Debbie, referring to the Japanese nuclear power plant that suffered a melt-down after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011. The uranium that fueled the plant came from Australia. Uranium mining now threatens Mulga Rock, the home of sacred healing sands that have been protected by the Spinifex for generations.

Storing the unstable and radioactive waste from nuclear power plants and nuclear medicine procedures is also a pervasive problem. Despite public outcry, this year the Australian government announced it had chosen a farm in South Australia’s Kimba as the site of a new federal nuclear waste dump. “We have been poisoned, and we don’t need the threat of being poisoned again by a nuclear waste dump,” says Aunty Sue. “It's not our right to condemn our children to the risk of leakages or damage or terrorist attacks forever. This is condemning them to a life of fear.”

Learn more and join the campaigns here:

ICAN Australia

Plan for a National Radioactive Waste Dump near Kimba, South Australia

Stop uranium mining in Western Australia

Article by Sarah Lord Anderson