Students from the University of Tuebingen at Museu do Aljube in Lisbon

From the Ship

The Salazar dictatorship still haunting Portugal

This article is part of a reportage series from selected ports of call of Peace Boat’s 102nd Global Voyage, seen through the eyes of students from the University of Tuebingen who joined the voyage.

University of Tuebingen students in Lisbon, Portugal

By Lea Gelfert, Juliane Hauschulz and Maximilian Wegener

Did you know that...?

...the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal was the longest dictatorship in Europe, lasting 41 years?

...the dictator Salazar was no longer in office for the last two years of his life due to his state of health, but he thought he was still in office? They even held fake cabinet meetings with him to make him believe he was still in power.

...it was only in 2015, 41 years after the end of the dictatorship, that Portugal's first museum dedicated to coming to terms with the dictatorship, the Aljube Museum, was opened?

|

The Salazar dictatorship (1932-1974) was based on a one party system, which used the secret police PIDE as a central instrument of violence and oppression against political opponents. Strongly modeled on Fascist Italy under Mussolini, the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar introduced “a new state”, “Estado Novo”, which was supported by a coalition of the military, the Catholic Church, business enterprises and large landowners. In addition, Portuguese colonies were ruthlessly exploited in order to fill the state coffers, which were always short of money. The regime worked systematically to depoliticize and pacify the citizens through the three Fs of Portugal: "Fado, Fátima e Futebol" - "music, religion and soccer". In 1974, though, broad popular protests finally ended the Salazar dictatorship. |

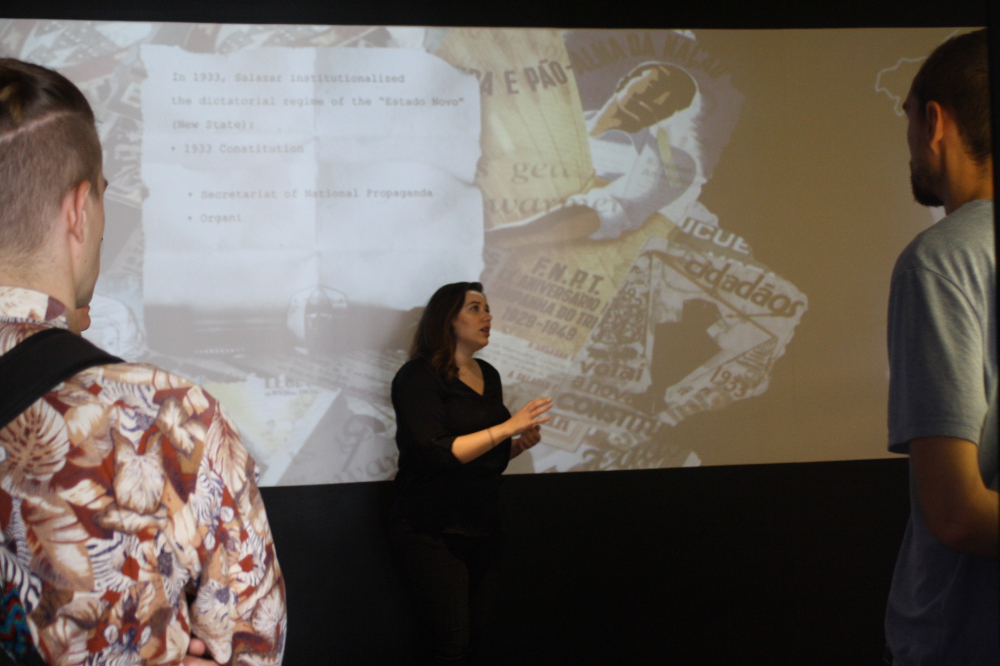

In order to better understand how the time of the Salazar dictatorship is remembered in Portugal today, we visit the Museu do Aljube in Lisbon. The exhibition rooms of the museum are located in a former prison which held political prisoners during the dictatorship.

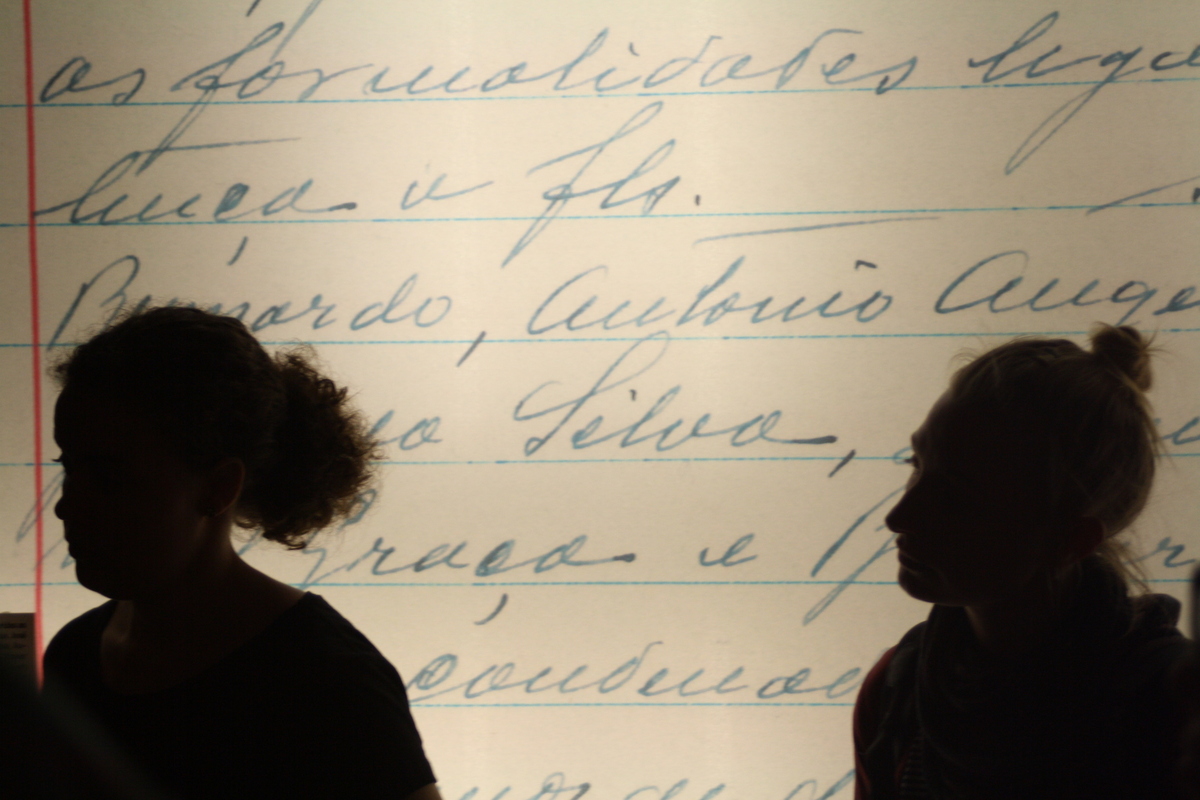

We meet staff member Elisabete Inácio who guides us through the exhibition. The whole atmosphere in the building is already oppressive. Windows are still barred, and one of the upper floors still contains three former prison cells. “Aljube” means “dungeon”. The exhibition vividly illustrates many aspects of the dictatorship. On one wall, we see former prisoners’ written recollections of what they experienced in this building.

Elisabete Inácio from Aljube Museum guiding students through the exhibition

Elisabete Inácio from Aljube Museum guiding students through the exhibition

Most of the written testimonies include haunting descriptions of mental and physical torture carried out by the infamous secret police of the time, PIDE. Some former prisoners also describe their experiences at Tarrafal, the most notorious Portuguese concentration camp for revolting military officers, republicans, communists and other opposition figures. Later, prisoners came to include members of the anti-colonial independence movements in Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau as well. The camp was built and operated along the lines of camps run by the Nazi regime - camp management, senior officers and guards even visited German concentration camps on so-called "training courses". To date, none of the perpetrators from Tarrafal have been convicted of their crimes.

In one part of the exhibition explaining how the dictatorship started, we see a photo of a large group of people giving the Nazi salute. Elisabete says that during tours for school groups, she often shows this picture to the pupils and asks where they think it was taken. The answer she usually hears is: Germany. But it was taken in Portugal. It shows how little children and young people in Portugal today learn about the Estado Novo. She also explains that in Portuguese schools, although the period of the dictatorship is addressed in the curriculum, the students hardly learn about the resistance and how the regime was overthrown in 1974.

Timeline of the Salazar era

Timeline of the Salazar era

How to remember unpleasant parts of history?

With the fall of the regime, officials wanted to declare this dark chapter closed, and many legacies of the dictatorship were destroyed. Elisabete tells us that the regime's supporters mostly faced prison sentences of a maximum of two years. Judges remained in office, and many former politicians were able to continue their careers. Meanwhile, victim groups received no compensation at all.

Elisabete explains that the opening of the Aljube Museum in 2015 was the first public display of the true nature of the Salazar dictatorship, and it inspired an increasing number of people who suffered under the Salazar regime to share their memories with the Museum. Some witnesses even bring their families to search for themselves in the photos displayed at the Museum.

At the end of our day in Lisbon, we have the impression that a critical reappraisal of Portugal's past and the Salazar dictatorship has so far been given too little space. And yet, progress is being made, albeit in small steps. Initiatives such as the opening of the Aljube Museum are certainly important steps.

Written testimonies of former prisoners

Written testimonies of former prisoners

This report from Lisbon is adapted from the radio series broadcasted by the Wueste Welle, Tuebingen. Listen to all podcasts here (in German)

Our partners in this project: University of Tuebingen and Berghof Foundation Tuebingen